What Does Skin Look Like Under a Microscope? (Images Included)

Last Updated on

From lotions and tanning beds, to deep-cleansing facials and clay masks—human skin seems to get a lot of attention for how it looks. But aside from looks, the skin is the largest organ of our body, and its functions play a huge part in keeping us healthy.

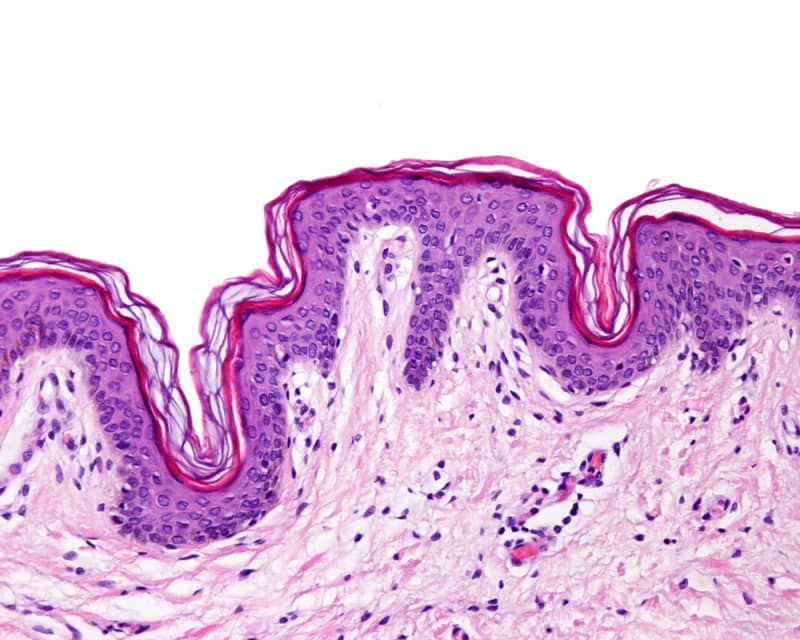

If you look at an image of skin under a microscope, you might mistake it for the cratered surface of an alien planet. Using very high magnification, as with an electron microscope, you can begin to see individual flat, scale-like cells that overlap one another—and maybe even spot a few free-roaming friendly skin mites.

If you’d like to dive deep and learn more about our fascinating skin, and all the ways it helps to protect us, keep reading!

The Layers of Human Skin

The main 7 layers of skin can be divided into two sections. The topmost 5 layers are all part of the epidermis, while the lower 2 make up the dermis. Beneath these 7 layers is the subcutaneous tissue, also known as the hypodermis. Here’s a breakdown of each layer visible to the naked eye, starting from the outermost.

Epidermis

The epidermis is made up of skin cells named keratinocytes. The deepest layer of the epidermis, the Stratum Basale, is where new, plump skin cells are created every day. As time passes, and new cells are made, the older ones get pushed up to the top, becoming flatter as they reach the surface.

Stratum Corneum

The stratum corneum is the outermost layer of skin. The keratinocytes here are flat and scale-like. They’re held together with carbohydrates and lipid, making them highly water resistant. The main function of this layer is to protect against microorganisms, such as bacteria, and the elements.

Stratum Lucidum

This very thin layer of skin is easily found with a microscope in areas with thick skin, such as the soles of feet and palms. The Stratum Lucidum protects these areas, which are most prone to damage, by decreasing the negative effects of friction. It also helps the skin to stretch.

Stratum Granulosum

The Stratum Granulosum is made up of diamond-shaped cells that secrete glycolipids that hold the cells together, but also act as a waterproof barrier to stop water from escaping the body.

Stratum Spinosum

Also known as the prickle layer, the Stratum Spinosum contains dendritic cells, which aid the body’s immune system. As well as helping with flexibility, the prickle layer also aids the outer layers of the epidermis to better tolerate the effects of friction. Keratinocytes mature during their journey through the Stratum Spinosum.

Stratum Basale

The Stratum Basale is the deepest layer of the epidermis. Here, keratinocytes are constantly being produced through mitosis, the division of cells. The calls are cuboidal, and they’re separated from the dermis by a thin membrane—the Basal Lamina.

The Stratum Basale also contains melanocytes that produce melanin, to protect the skin against UV rays from the sun. Melanin is what gives skin its pigment.

Dermis

The dermis is made up of elastin (elastic fibers), and collagen (protein fibers). Elastin gives skin elasticity and suppleness, while collagen helps to strengthen it. The dermis is also home to blood vessels and nerves, sweat glands, hair follicles, and sebaceous glands.

Papillary Layer

The papillary layer’s main function is to provide nutrients to the skin through capillaries. The blood flow also helps with regulating body temperature. Lastly, it contains sensory receptors that can detect temperature, texture, pain, and pressure.

Reticular Layer

The reticular layer is the deepest layer of the dermis, and the last layer of skin before the hypodermis. As with the papillary layer, it contains collagen to help strengthen the skin, and elastin to aid with elasticity. This layer also contains hair follicles, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands.

Hypodermis

The hypodermis, also known as the subcutaneous tissue, is the deepest layer of skin. It’s mostly made up of fat and connective tissues. It helps to regulate body temperature, and it’s also home to larger nerves and blood vessels.

Aside from providing insulation, the hypodermis also stores fat that sticks the outer layers of skin to the flesh and bone underneath. The hypodermis layer also aids in hormone production, and generally protects the body by adding a layer of cushioning against impacts.

Are Skin Cells Dead?

The outermost 25-30 layers of skin cells in the epidermis are actually dead. New skin cells are constantly being produced in the Stratum Basale. As this happens, the older cells get pushed up to the top. Therefore, the topmost layers of skin cells only act as a barrier to water and foreign microorganisms.

How Thick is Human Skin?

Skin is thicker in some areas, and thinner in others. On average, it’s only around 0.07 inches thick, but it covers approximately 20 square feet, and weighs just over 6 pounds.

Is Human Skin Permeable to Water?

The lipid content secreted by the cells in the epidermis gives skin a waterproof quality, as well as low permeability. For this reason, it’s very difficult for water and other substances to enter the body through the skin. This is what makes the skin so good at protecting us against most potentially harmful foreign substances.

Can You Absorb Oxygen Through Your Skin?

As strange as it seems, it is possible for some areas of your skin to absorb oxygen. Mostly, it is the topmost layer of the skin, the epidermis, which is in direct contact with the air, that absorbs the oxygen it needs. This part of the skin is composed mostly of dead skin cells, however, and the rest of the body relies on getting oxygen through a continuous blood supply.

Final Thoughts

Depending on the strength of the microscope you use, the skin can look like a landscape of layered scales or, with a weaker microscope, a surface that’s crisscrossed with lines and dotted with pores. Hairs will appear large and thick, and if you’re lucky, you may even spot a few skin mites!

But, as alien as our skin close-ups may seem, the largest organ of our bodies protects us from harm every day.

Featured Image Credit: Piqsels

Table of Contents

About the Author Cheryl Regan

Cheryl is a freelance content and copywriter from the United Kingdom. Her interests include hiking and amateur astronomy but focuses her writing on gardening and photography. If she isn't writing she can be found curled up with a coffee and her pet cat.

Related Articles:

How to Clean a Refractor Telescope: Step-by-Step Guide

How to Clean a Telescope Eyepiece: Step-by-Step Guide

How to Clean a Rifle Scope: 8 Expert Tips

Monocular vs Telescope: Differences Explained (With Pictures)

What Is a Monocular Used For? 8 Common Functions

How to Clean a Telescope Mirror: 8 Expert Tips

Brightfield vs Phase Contrast Microscopy: The Differences Explained

SkyCamHD Drone Review: Pros, Cons, FAQ, & Verdict