What Does a Worm Look Like Under a Microscope? Tips, Facts, & FAQ

Last Updated on

Viewing objects under a microscope is always interesting since you can see things too small to be seen with the naked eye. It is especially true for worms, tiny creatures living in the soil.

Typically, if you put a worm on a microscopic slide, you’ll see the segments of its long, thin body. In addition, its mouthparts will be visible, as well as the tiny bristles (setae¹) that help it move and anchor itself. If the worm is a female, you may also be able to see her egg sac.

Let’s take a deep dive into what a worm looks like under a microscope and how you can get the best view.

How Does an Earthworm Look Under a Microscope?

Before you learn what you’ll see if you put a worm under a microscope, it’s essential to know the anatomy of these creatures. Different species of worms have different colors and markings, so no two look exactly alike. In addition, since some species have a dark epidermal covering, you might not be able to see the internal organs through it.

Earthworms are segmented, which means their bodies are divided into sections. Each section is called a “ring” or “annulus.” For example, the front end of an earthworm is called the prostomium. It is followed by the peristomium, which surrounds the mouth. Next are up to 150 body segments, each with its internal organs. Finally, the back end of an earthworm is called the clitellum.

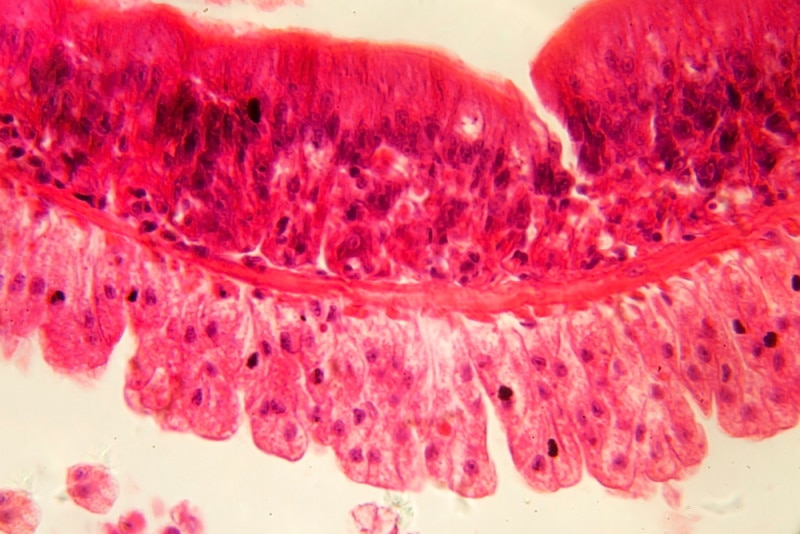

One of the first things you’ll see if you put an earthworm under a microscope is the segments on its body. The segments will appear to be twisting and moving about. If there’s good lighting, you might be able to see some internal organs, such as the vessels. However, the dark epidermis often makes it difficult to see much else.

If you look at the anterior end of the earthworm, you’ll see a pointed and narrow prostomium. The prostomium is used to sense the environment and help the creature move forward. You’ll notice a distinct segment in the middle that’s lighter in color than the other segments. It also seems swollen as compared to surrounding segments. The segment is called the clitellum and helps the earthworm mate.

Besides these parts, you might also be able to see the setae of the earthworm under the microscope. The setae are tiny bristles that help the creature move and anchor itself in place. If you look at a cross-section of an earthworm, you’ll notice that it has a hollow tube running the length of its body. It is the alimentary canal, and it’s where food is digested.

The earthworm also has a pair of hearts that pumps blood through its body. If you look at the earthworm under a microscope, you might be able to see the movement of these hearts. You’ll also notice a series of tiny pores along the length of the earthworm. These are called nephridiopores¹, and they help remove waste from the creature’s body.

How Do Other Worms Look Under a Microscope?

What you see under a microscope will depend on the anatomy of the worm you are looking at. Some have long, thin bodies, while others may be short and stocky.

Likewise, some worms are segmented while others are not. The most noticeable difference, however, will be in the number of legs each type of worm has.

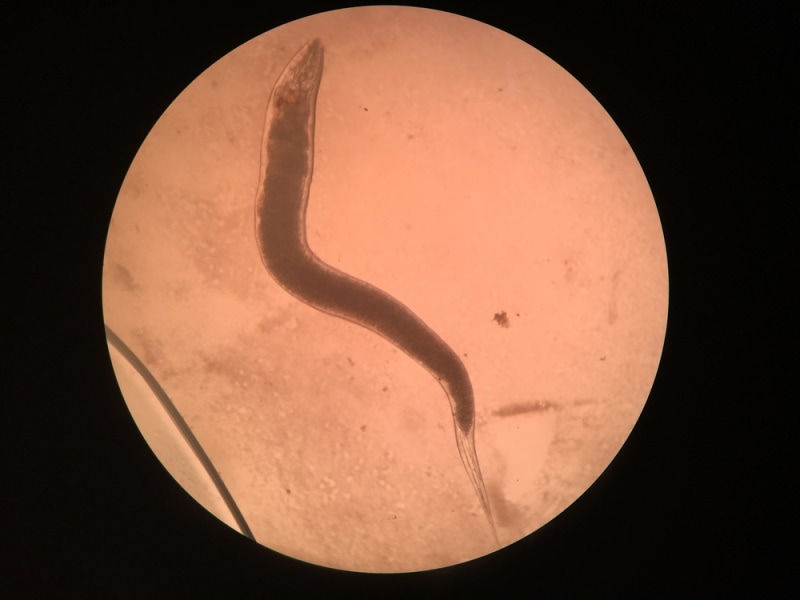

Eelworms

Eelworms are small, unsegmented worms that often live in the soil. Since these are much smaller than earthworms, you might find it hard to differentiate their body parts under a microscope.

However, if you look closely, you can see them move around as a colony.

Planarian Flatworms

Planarian flatworms are among the most common worms found in freshwater habitats. They get their name from their flat, oval-shaped bodies. When you look at them under the microscope, you’ll notice that they have a pointed tail and broad anterior section. However, if you look closely, you may also see the eyespots. These are present in the head region and help the worm orient itself.

Roundworms

When you see a roundworm under a microscope, you’ll first notice the transparent epidermis. The worm’s body is long and slender and tapers towards the end. If you’re using a microscope with higher magnification, you’ll also be able to see a mouth part on the worm’s anterior end. Plus, you can see an intestine that runs through the body. Dissecting the roundworm will allow you to see the internal organs more clearly.

How Does a Dissected Worm Look Under a Microscope?

Dissection means to cut something open to study it. In a scientific setting, dissection often refers to cutting an animal or plant open to study its internal parts. Dissections are performed both in classrooms and in research laboratories.

Dissecting a Worm

Let’s take an earthworm to explain the process. If you want to see the internal organs of the earthworm clearly, you’ll have to dissect it before putting it under a microscope. You’ll need the following materials:

- Dissecting pins

- Dissecting tray

- Forceps

- Dissecting knife or scissors

First off, put the earthworm on the dissecting tray. Make sure its dorsal side is facing upward. The dorsal side is the side with the earthworm’s bumps.

Now, take the forceps and grab the earthworm by its head. Pin the head to the tray with the dissecting pins.

Next, use the knife or scissors to make a cut along the length of the earthworm’s body. Be careful not to cut too deeply. You just want to cut through the skin.

Pull the epidermis (skin) apart using forceps so that you can see the earthworm’s body cavity.

Observing Under a Microscope

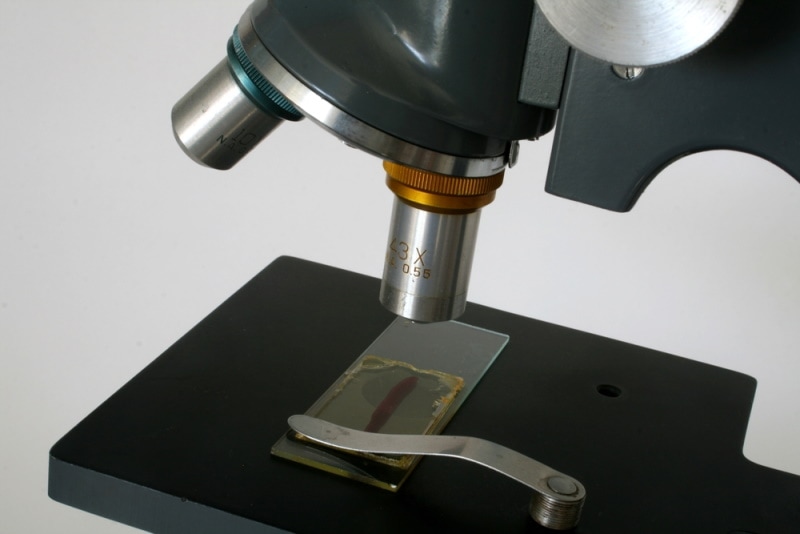

Now that you have your worm all prepped for observation, you can view it under a microscope.

- Aortic Arches: These are the ”hearts” of the earthworm. There are five pairs of aortic arches, and they pump blood throughout the body.

- Reproductive Organs: You’ll also see the reproductive organs near the heart. They are tiny, lightly colored organs.

- Pharynx: The pharynx is a muscular organ that helps the earthworm eat. It is also lightly colored and has plenty of muscles.

- Central Nerve Cord: The central nerve cord is a long white cord that runs the length of the earthworm’s body. This is the worm’s ”brain”. You’ll have to move the intestine aside to see it.

How to Get the Best View of a Worm Under a Microscope?

The level of detail and clarity you see in a worm under a microscope depends on the quality of your microscope and how expertly you use it. Here are some microscopy tips to get the best view of your specimen:

Start With the lowest Magnification

When setting the focus, it’s always best to start with the lowest magnification. Then, once you have a clear image, you can increase the power (magnification) until you see the details you’re looking for.

If you start at high magnification, getting a clear image will be more difficult.

Use Brightfield Illumination

For the best contrast and detail, use brightfield illumination. It is the standard setting on most microscopes. In brightfield, the light shines up through the specimen from below and is then reflected into your eye by the microscope’s optics.

To increase the contrast even further, you can use a technique called phase contrast. In phase contrast, a special condenser bends the light as it passes through the specimen. It produces a halo effect around objects, making them appear brighter against the dark background.

Adjust the Light Source

If you’re not getting enough light, adjust the intensity of the light source. You can also change the illumination through a condenser or intensity control.

For this, consult your microscope’s user manual. Most microscopes have knob controls to adjust the light.

Final Thoughts

Usually, when you view a worm under a microscope, you’ll only see a long, skinny creature with no legs. However, if the worm has a transparent epidermis, you might be able to see its guts, which look like a series of translucent tubes.

If you want a better view, you can dissect the worm. It will give you a clear view of the creature’s internal anatomy, including its muscular, reproductive, and nervous systems. Besides the worm’s anatomy, your expertise in handling a microscope and the microscope’s magnification will also determine how much detail you can see.

Featured Image Credit: Michael LaMonica, Shutterstock

About the Author Jeff Weishaupt

Jeff is a tech professional by day, writer, and amateur photographer by night. He's had the privilege of leading software teams for startups to the Fortune 100 over the past two decades. He currently works in the data privacy space. Jeff's amateur photography interests started in 2008 when he got his first DSLR camera, the Canon Rebel. Since then, he's taken tens of thousands of photos. His favorite handheld camera these days is his Google Pixel 6 XL. He loves taking photos of nature and his kids. In 2016, he bought his first drone, the Mavic Pro. Taking photos from the air is an amazing perspective, and he loves to take his drone while traveling.

Related Articles:

How to Clean a Refractor Telescope: Step-by-Step Guide

How to Clean a Telescope Eyepiece: Step-by-Step Guide

How to Clean a Rifle Scope: 8 Expert Tips

Monocular vs Telescope: Differences Explained (With Pictures)

What Is a Monocular Used For? 8 Common Functions

How to Clean a Telescope Mirror: 8 Expert Tips

Brightfield vs Phase Contrast Microscopy: The Differences Explained

SkyCamHD Drone Review: Pros, Cons, FAQ, & Verdict