Winter Wren: Field Guide, Pictures, Habitat & Info

Last Updated on

![]()

Up until 2010, we used to think the Winter Wren was the same species as the Eurasian Wren and the Pacific Wren.1 Of course, there were some minor differences, but we thought they were evolutionary changes ordinarily caused by climatic variations.

Eventually, researchers studied them further. And that’s how they discovered all three species were genetically different. Read on if you’d like to learn what else they discovered.

Quick Facts about Winter Wrens

| Habitat: | Evergreen Coniferous, Deciduous Forests |

| Diet: | Insects, Berries |

| Behavior: | Territorial, Ground Forager |

| Nesting: | Cavity |

| Conservation: | Least Concern |

| Scientific name: | Troglodytes hiemalis |

| Lifespan: | 2 years |

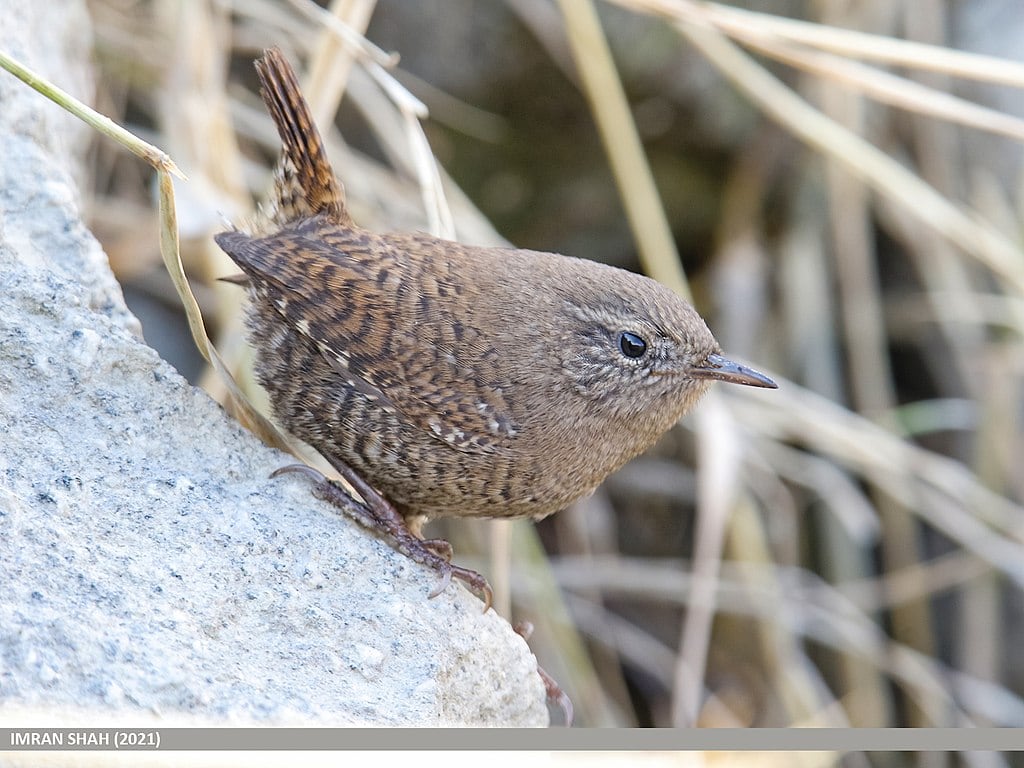

Winter Wren General Description

The Winter Wren is one of the many songbirds that call the North and South American continent home. It is relatively tiny, has a very short lifespan, and is territorial. Like all songbirds, it loves singing and perching. That is why it belongs in the Passeriformes order. Being small means it’s always at the bottom of the food chain, wherever it goes.

Winter Wren: Range, Habitat, Behavior, Diet & Nesting

Range

If you’ve ever visited the coniferous woodlands found next to the Atlantic Ocean, there’s a very high probability that you’ve come bumped into a community of Winter Wrens living in that area. And even if you never got the chance to see them, you can still find some in one of Canada’s westernmost provinces, British Columbia.

The Winter Wrens are a partially migratory species. Don’t let that name fool you because they’ll bail the minute the temperatures drop past zero, or if they are ready to start breeding. But rarely do they leave the North American continent, as they usually relocate to the northeastern parts of Mexico or the southeastern regions of Canada.

Nonetheless, for most of the year, a large population of this species will be found in the western and eastern territories of North America.

How big their territories are will depend on the situation at hand. If there are no apex predators around, this bird can inhabit a significantly large territory.

Habitat

The Winter Wren will either go for the deciduous forest or one described as evergreen and full of old-growth trees. In addition, the altitude and temperatures have to be optimal. By that, we mean milder degrees on the scale and lower elevations.

When the time’s right and they are looking to breed, they’ll move from the deciduous forest to one defined by coniferous trees and its proximity to a water body. The underlying layer of vegetation should be a dense thicket, with no signs of disturbance.

Winter Wrens like to build homes closer to the ground. If they sense there might be a predator scouting the area, they’ll bail immediately and never look back. And they know cats like to make a meal out of them. For that reason, if you’re trying to lure some to your backyard, and you’re a cat person, you better find a way to make sure they don’t see it anywhere near their feeders.

Behavior

The way the Winter Wren moves while foraging for food is similar to how mice hunt for food. They’ll hop and scamper through the decaying logs and even upturned roots as if they’ve forgotten how to walk like normal birds. They also seem to have a lot of energy, as they’ll even bob their bodies, the same way we do while squatting in the gym.

Compared to other species, their flying is not that great either. They often beat those tiny wings several times per second, but only manage to cover a very short distance.

Anytime they manage to find food from foliage, they pick it up using their bills, throw it up, and then jump to grab it. If it’s during the breeding season, the males that won’t be foraging will be seated, singing with vigor to attract a mate. That song will catch the attention of the right partner, compelling her to get closer and enter his territory.

Diet

A lot of bird species hunt insects during their breeding season. The insects not only have the requisite amount of protein needed, but also a high-water content to keep the birds and their young ones healthy.

Winter Wrens are different in the sense that they feed on insects all year round. That’s actually the reason why most sources categorize them as insectivores even though they sometimes eat berries and even fish. The only time they’ll show up at your feeder is during winter, when most insects are cooped up in tree holes or under rocks, trying to battle the freezing temperatures.

Nesting

The males are usually tasked with building nests. They’ll start working on them even before they get a mate, as part of their courtship rituals. Unlike most species, the male Wren normally builds more than one nest around the same breeding site. When his partner shows up, she’ll choose the most suitable box of them all, and abandon the rest.

Their breeding season starts around April and ends in July. This might be different in some regions, seeing as we all experience different climatic conditions annually. All we know is that Wrens that have built homes far south frequently don’t migrate. And that’s why their nesting activities customarily begin in March.

Choosing a nesting spot is not an easy job even for a bird. They often spend a lot of time scouting the area, to make sure there are no predators in the vicinity. Also, let’s not forget the fact that the male Wren has to construct more than one nest to please a potential partner. It’s due to that whole daunting experience that they usually decide to go back to their original breeding grounds.

That being said, if they find that their nest has been occupied, removed, or damaged, they’ll pack all their belongings and move to a different location. Preferably very far away from that spot.

Eggs

In total, a female Wren will lay four to seven eggs. Four, if the conditions are not optimal, and seven, if they have more than enough to survive. The eggs are mainly white, with some reddish-brown markings at the larger end.

The incubation period is about 2 weeks, and the younglings will be ready to explore the world 19 days after hatching. As dependents, they’ll be fed by both parents and be protected from any predator or intruder.

How To Find a Winter Wren: Birdwatching Tips

What To Listen For

First off, Wrens come in various species and subspecies. But what we appreciate about them is the fact that they all sing whenever they feel the need to establish dominance, send warning signals to intruders, or lure mates. The songs are annoyingly loud, last 5 to 10 seconds, and have about 40 different notes.

What To Look For

This particular species looks like a plump round ball. Its black-colored beak is not unusually small for a songbird, but remarkably thin. It likes to hold the tail up, making it look like a stubby nail. The wingspan is about 4.7 to 6.3 inches, and it weighs 0.3 to 0.4 ounces. If you’re lucky to get close, you’ll realize the plumage has a combination of brown and white colors.

When To Look

The Winter Wren is bubbly. They are not as active during the cold season as they are during summer, but you can still catch them singing very early in the morning. While other birds are busy foraging for food, they’ll be perched on low tree branches, swinging their tails and singing at the top of their lungs. You’ll for sure hate them if you’re not a morning person, and they decide to station themselves right outside your window.

Attracting Winter Wrens to Your Backyard: Tips & Tricks

If you’d like the Wren to visit you, you should be willing and able to provide the usual essentials needed for survival. They include:

- Food

We’ve already told you that Wrens love insects more than anything. They’ll sample berries once in a while, but insects are their staple. Obviously, you cannot walk into a grocery store and ask the cashier to sell you some insects. What you should do is avoid using insecticides or removing the webs built by spiders. In other words, make your home an insect hub.

- Water

Have you ever heard of a living organism that hates water? Water is life and this Wren species understands this. They’ll need water to stay hydrated and to take a bath. Yes, birds do bathe, and they love it. So go ahead and install a fountain in your yard, or just leave a small bucket outside. Remember to change it at least three times a week.

- Shelter

Plant some shrubs here and there. Something that will grow into a thicket that can provide sufficient shelter when they need to hide from predators or protect themselves from harsh weather elements.

- Nesting site

One of the things that makes the Wren different from other birds is their unusual nesting habits. After scouting suitable grounds, they’ll settle for a spot that just looks weird. It can be a nasty-looking crevice, a hole in a tree, a cluttered garage, or a flower pot. So just place a few grass clippings, webs, twigs, feathers, or moss near any one of those places, and you’ll soon see one.

Winter Wren Conservation: Is this Bird Threatened?

Lucky for us, the Winter Wren is one of the few bird species that are still widespread. We’ve also been told that their numbers are fairly stable, so there’s no cause for concern. In the past, several species were affected by the chemicals used in the production of various insecticides and pesticides. The Environmental Protection Agency had to step in, as some species almost went extinct.

Final Thoughts

Did you know the Americas are considered the primary home of the Wren species? We have more than 80 different species and subspecies living here, and only one living outside the continent. That one species is the Eurasian Wren.

If you feel like there’s something we left out, feel free to drop us a line.

Featured Image Credit: Rawpixel

About the Author Robert Sparks

Robert’s obsession with all things optical started early in life, when his optician father would bring home prototypes for Robert to play with. Nowadays, Robert is dedicated to helping others find the right optics for their needs. His hobbies include astronomy, astrophysics, and model building. Originally from Newark, NJ, he resides in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where the nighttime skies are filled with glittering stars.

Related Articles:

10 Types of Hummingbirds in Arkansas (With Pictures)

8 Types of Hummingbirds in Nebraska (With Pictures)

5 Types of Hummingbirds in Idaho (With Pictures)

3 Types of Hummingbirds in Mississippi (With Pictures)

8 Types of Hummingbirds in Kansas (With Pictures)

5 Types of Hummingbirds in West Virginia (With Pictures)

5 Types of Hummingbirds in Ohio (With Pictures)

Where Do Nuthatches Nest? Nuthatch Nesting Habits Explained