Muzzleloader Scope vs. Rifle Scope: What’s the Difference?

Last Updated on

There are distinct differences between muzzleloader scopes and rifle scopes. Knowing what those differences are can be important if you are trying to mix and match by putting a muzzleloader scope on a rifle or vice versa. Whether you’re a muzzleloader shooter looking for a scope to buy or a modern rifle shooter, making sure you get the right scope for your needs is critical to shooting with precision and accuracy.

Our goal in this article is to explain the differences between these different types of scopes and why they are designed the way they are. We’ll start with rifle scopes as the standard and then explain how muzzleloader scopes are different.

A Scope’s a Scope, Right?

In theory, yes, muzzleloader and rifle scopes operate in much the same way and can be interchangeable in some cases, but there are key differences in the demands of the two firearm styles that result in two very different scope designs.

Overview of Rifle Scopes

Riflescopes provide magnification for a shooter that helps them achieve more precise shots from a longer range. They achieve magnification either using lenses or a combination of lenses and prisms. In general, rifle scopes will provide magnification between 3x and 20x, though scopes that offer either more or less magnification do exist.

via precisely-machined rings that clamp to a rail that is attached to the top of the rifle. The rings hold the scope in place while the rail holds the rifle and scope together.

Basic Scope Mechanics

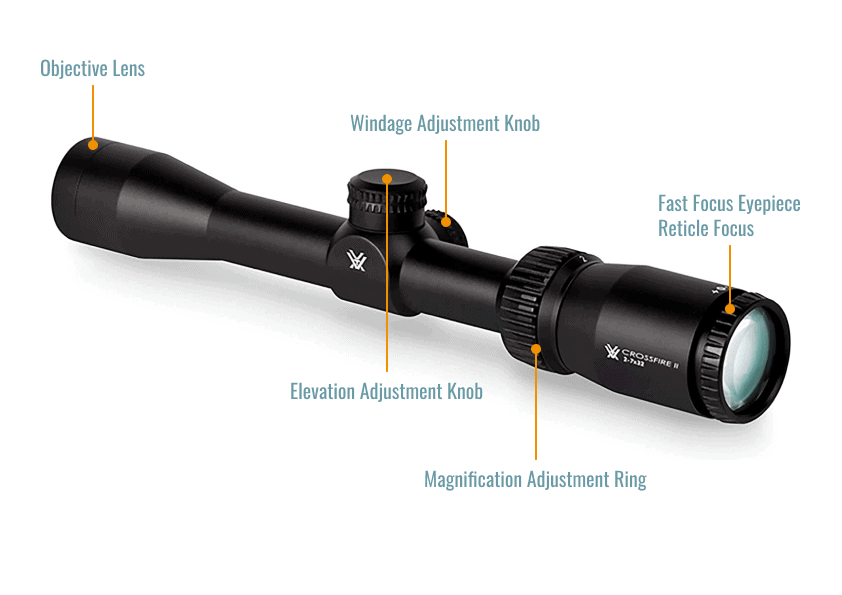

The lens that a shooter looks through is called the ocular lens, and the lens on the other end of the scope is called the objective lens. The larger the objective lens, the more light it can let in and the brighter the image through the scope will be, but the more space the scope will take up on top of the rifle, and the heavier the scope.

Scopes with variable magnification (variable zoom) are described with their magnification range and their objective lens diameter like this example: 3x-9x 32mm. This scope has a minimum magnification of 3x and a maximum magnification of 9x, with an objective diameter of 32mm.

Anytime you are shooting with a scope, there are going to be adjustments that you need to make to it after it’s mounted to ensure that your bullets are hitting exactly where the center of the reticle is when you are aiming it. This process is called zeroing your scope in or sighting it in, and is done by making small left-right and up-down adjustments using two small knobs on the scope.

Rifle Scopes and Recoil

One of the most common concerns with buying a new scope is whether it can withstand the recoil of the firearm you are purchasing it for. Smaller caliber rifles have relatively little recoil, while larger caliber rifles will have significantly more.

If you throw a piece of cheap glass on a .50BMG, your scope may only last for a handful of rounds before it loses zero or breaks. Rifle scopes are designed to withstand recoil of common rifle calibers like .223, .308, and .270.

Parallax

Parallax can be a bit tricky to explain, but it’s just a word for how things closer to you seem to move faster than things farther away. This visual trick becomes a real problem when you’re trying to line up a reticle that’s only inches from your eye with a target that is hundreds of yards out.

Rifle scope reticles are usually designed to minimize the effect of parallax when aiming at a target 100 yards away. Scopes with higher magnification may aim to minimize parallax at 200 or 400 yards.

Reticle Design

Rifle scopes reticles usually have standard crosshairs plus some other lines or markings that can help a shooter adjust their shot on the fly. A common addition to a reticle is a BDC ladder. “BDC” stands for Bullet Drop Compensation. As a bullet flies through the air, it slowly falls. So if you have zeroed your scope in at 100 yards, then try to shoot at 200 yards, your shots will land a little lower than the center of your scope.

A BDC ladder provides etched lines on your reticle that show you where to place your shots so that the bullet hits where you want it at different distances.

Eye Relief

Eye relief refers to the distance that your eye should be from the ocular lens in order to see the full picture from the scope clearly. Making sure your scope has the right amount of eye relief for how much recoil your rifle has will prevent you from getting kissed by your scope, and allow you to get into the shooting position you find most comfortable.

It’s common to see eye relief between 3 inches and 4 inches on most rifle scopes, but they can go as low as 1.5 inches on a lower magnification scope intended for small caliber shooting.

- Designed for long range shooting

- Comfortable amount of eye relief

- BDC ladder allows for shots up to 1000 yards

- Not built to withstand heavy recoil

- Parallax can be bad at shorter distances

Overview of Muzzleloader Scopes:

The basic mechanics and operation of muzzleloader scopes are the same as rifle scopes; they both have an objective lens, ocular lens, and use either lenses or prisms to provide the magnification. Most muzzleloader scopes will top out at around 9x magnification, both because of the maximum distance that muzzleloaders can shoot and because of the strong recoil.

Muzzleloaders vs. Rifles

Speaking generally, the payload from a muzzleloader is going to be larger than any rifle caliber (except .50BMG) and the firearms are operated differently. Loading a muzzleloader is done through (you guessed it) the muzzle, and the process is a lot more involved than a bolt-action rifle.

Historically, muzzleloaders tend to pack a lot of punch over a short distance. While modern muzzleloader projectiles have a conical shape and a decent ballistic coefficient, they still don’t quite stand up to the long-range precision of the common rifle calibers. Here are the key differences between muzzleloader scopes and rifle scopes.

Muzzleloader Scopes and Recoil

Muzzleloaders have stronger recoil than rifles as a general rule. Often, the kick from a muzzleloader can be immensely powerful. This recoil wreaks havoc on the sensitive glass inside a scope, and for the most part only scopes that have been designed to withstand that recoil should be used on a muzzleloader. That said, rifle scopes designed for .308 or .270 recoil are sometimes “over-engineered” to where they can hold up fine to a muzzleloader.

If you’re considering using a rifle scope on your muzzleloader, you’ll want to check what caliber the scope was designed for.

Parallax

The trick with parallax on a scope is that it will get worse the further you get from where the scope is designed to minimize parallax. For example, on a rifle scope designed for 100-yard shooting, if your target is closer or further than 100 yards, you’ll start to notice more and more parallax.

Muzzleloaders are generally not used for long-range shots, and so most manufacturers of muzzleloader scopes design the parallax to be at its minimum at 50 yards instead of 100.

Reticle Design

The trick with BDC ladders is that the amount the bullet drops over a certain distance changes based on the size and velocity of the projectile. BDC ladders on muzzleloader scopes reflect the size and velocity of specific muzzleloader shots, which are very different from those of a rifle, even if the caliber of the bullet is the same.

Eye Relief

Remember when we said the kick from a muzzleloader can be immensely powerful? Well, the last thing you want is the scope slamming into your head with all that recoil and giving you a third eyebrow. Muzzleloader scopes are designed to give a longer eye relief so you can keep the firearm further from your eye while shooting. You should see at least 4 inches of eye relief on a muzzleloader scope.

- Designed to withstand stronger recoil

- Parallax is better at shorter distances

- BDC Ladder is better at shorter distances

- Longer eye relief

- Not as high of magnification

- Parallax is worse at longer distances

- BDC ladder is less useful at longer distances

Other Factors to Consider

If you’re still wondering what the right option is for you, chances are you already have a rifle scope in mind to put on your muzzleloader, or a muzzleloader scope you want to put on your rifle. Here are a few more things to consider.

What Type of Scope Do You Need?

If you’re shooting with a muzzleloader you need a scope that can stand up to the recoil. If you have a rifle scope that is rated to a larger caliber, then it may stand up to a muzzleloader just fine, but you’ll want to research the exact scope you have in mind to make sure it will be as tough as you need it to be.

You can use a muzzleloader scope on a rifle and vice versa, the question just becomes how well the scope will be optimized for what you’re using it for. Using a muzzleloader scope for 800-yard precision shooting isn’t going to work as well as for 100-yard target practice, for example.

You also need a scope that has enough eye relief that you’re not giving yourself a concussion every time you pull the trigger if you’re shooting a muzzleloader. If you’re shooting a rifle, longer eye relief isn’t always better; you want to find a scope that has the magnification you want with eye relief that allows you to choose a comfortable position while shooting.

What Type of Scope Do You Want?

Even if you can use a muzzleloader scope on a rifle and a rifle scope on a muzzleloader, do you really want to? If you have a scope with a BDC ladder for a .223 round that goes up to 1000 yards, is that really what you want to see every time you line up your sight picture for a 50-yard shot with a muzzleloader?

Using a scope designed for one type of firearm on a different type can work in a pinch but the features of the scope become drawbacks. Parallax that’s perfect at 50 yards becomes unbearable at 200, and a rifle scope that isn’t damaged by the stronger recoil may still lose its zero more quickly on a muzzleloader.

Comparing Price

Prices are fairly comparable between the two scope types, so you aren’t likely to save money by purchasing one type over the other unless you’re looking to use the scope on multiple firearms. Considering how involved the mounting and zeroing process can be, that seems like an awful lot of trouble for the amount of money you would be able to save.

Conclusion

At first glance, there doesn’t seem like there’s much of a difference between muzzleloader scopes and rifle scopes, but the deeper you look the more difference you’ll find, and some of those differences can make a significant difference in how effective the scope and rifle combination you choose will be.

You might also be interested in: 6 Best Scopes for .300 Win Mag — Reviews & Top Picks

About the Author Robert Sparks

Robert’s obsession with all things optical started early in life, when his optician father would bring home prototypes for Robert to play with. Nowadays, Robert is dedicated to helping others find the right optics for their needs. His hobbies include astronomy, astrophysics, and model building. Originally from Newark, NJ, he resides in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where the nighttime skies are filled with glittering stars.

Related Articles:

How to Clean a Refractor Telescope: Step-by-Step Guide

How to Clean a Rifle Scope: 8 Expert Tips

Monocular vs Telescope: Differences Explained (With Pictures)

How to Clean a Telescope Eyepiece: Step-by-Step Guide

What Is a Monocular Used For? 8 Common Functions

How to Clean a Telescope Mirror: 8 Expert Tips

Brightfield vs Phase Contrast Microscopy: The Differences Explained

SkyCamHD Drone Review: Pros, Cons, FAQ, & Verdict